The New York Times has a human interest story, “Along Hurricane Dorian’s Tortured Path, Millions are United in Fear,” a fine example of quality upper-crust American journalism, against which it is interesting to contrast “’Waffle House Index’ is a real thing during disasters. How does the restaurant chain do it?” by a writer from the lowly Pensacola News Journal.

The New York Times has a human interest story, “Along Hurricane Dorian’s Tortured Path, Millions are United in Fear,” a fine example of quality upper-crust American journalism, against which it is interesting to contrast “’Waffle House Index’ is a real thing during disasters. How does the restaurant chain do it?” by a writer from the lowly Pensacola News Journal.

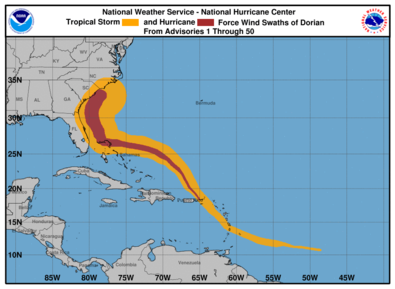

At the New York Times, things go wrong right away. A tortured path is one that is difficult to traverse. The videogame “Call of Duty” uses the expression correctly to name a scenario in which a band of heroes must cross 2000 miles of dangerous territory infested by Nazi Zombies. But Hurricane Dorian faces no peril or difficulty on its path. Dorian is doing just as it likes. Perhaps the Times meant to say that Dorian’s path is tortuous, one marked by repeated twists and turns, which is true. Tortured, tortuous – easy mistake, right? My guess, though, is that the paper fell into talking nonsense because it couldn’t resist a third related idea: of Dorian torturing millions who are “United in Fear,” which is also the thrust of the article that follows.

Here’s Norma Lemon, “the owner of a Caribbean-themed restaurant on the South Carolina coast,” where one or more of the four Times correspondents on this story may have stopped for a good fat lunch, then thought to rope in their good hostess for material.

Asked about the plight of the storm-struck Bahamas Ms. Lemon says:

“We are in the same boat, pretty much…They’re saying 175 mile-per-hour winds. You’re thinking about people in the Bahamas and other places that’s really getting it. And then you think that it’s coming to you.”

After that doubtless sincere but brief expression of concern for others, Ms. Lemon settles into her own problems, like any normal person. Hurricanes have forced her to evacuate three times in the last few years, and she’s fed up at the thought of having to run for it one more time.

According to the mind-readers at the New York Times, though, this means that Ms. Lemon:

“was also aware of the strange way that a brutal threat like Hurricane Dorian…can bind a disparate community across states and nations. She knew that all of them…were inhabiting a distinct universe of worry.”

I can imagine a startled Ms. Lemon rapping out a sharp “What the hell?” at the presumption with which the Times writers have stuffed these inflated pseudo-profundities into her mouth. A random collection of strangers who happen to confront some passing common threat or concern, and who may occasionally think about others in the same plight, does not for that reason become “a community,” however disparate, much less “a distinct universe of worry,” whatever that means.

On we go:

“It was a familiar feeling of dread for a region where residents mark their lives by the hurricanes they have survived. Their relationships with storms, with their power to kill and destroy, are primarily built on fear.”

Oh come off it! I have old friends, immigrants, who’ve run a general store near Vero Beach, on the middle Atlantic coast of Florida – prime hurricane territory – for more than forty years. I’ve never heard them gripe about “familiar feelings of dread,” much less to “mark their lives by the hurricanes they’ve survived,” nor to moan fearfully about “their relationships with storms.”

This whole extremely fanciful notion of having “relationships with storms” would indeed occur mainly to bookish folk who’ve never much had to deal with physical hazards of any sort. Working people like Ms. Lemon or my friends in Vero Beach are more likely to be putting up the storm shutters. Having chosen to make a living in hurricane-prone areas, they tend not to be overcome by dread when a hurricane does roll around. Nor do any of the other people interviewed in the Times article. Here is the charmingly relaxed Ms. Renora Johnson, 69, of Cocoa, Florida, who didn’t evacuate during Hurricane Irma two years ago because “that seemed like too much of a hassle.” And here’s Mr. Stephen Neville, a lineman for Florida Power and Light:

“When we hear there is a storm, we are walking around the yard, high-fiving each other saying, ‘Bring it on!… Everybody is pumped up. We are like dogs in a cage, ready to attack.”

Splendid fellow!

Here’s one last example of the way the Times’s ideological fixations and intellectual pretensions lead it into literal nonsense. The paper is keen to play up the multiculturalism of Ms. Lemon’s restaurant, linking perhaps to the communities “across states and nations” that it imagines spring up around every hurricane.

“The menu emphasizes the easy cultural harmony between the Caribbean and this stretch of Carolina coast, where Gullah accents lend what to an untrained ear might feel like an island flavor.”

The writers couldn’t resist bringing in the fashionably multicultural “Gullah accents,” and end by confusing between the senses of taste and hearing, with the ridiculous image of an ear listening to the flavor of food. But it doesn’t matter! It’s as if the words are ritual chants designed to stupefy with a vague sense of well-being and one’s cultural and moral superiority, though unconnected to any clear images or ideas.

With what a sense of relief and anticipation one turns at last to “’Waffle House Index’ is a real thing during disasters. How does the restaurant chain do it?” by Annie Banks of the Pensacola News Journal:

“PENSACOLA, Fla. – As preparations got underway late last week throughout the state of Florida in advance of Hurricane Dorian, a small but dedicated team of employees at the Waffle House headquarters just outside Atlanta quietly began gearing up for preparations of their own.

- Assemble “jump teams” of operators from Waffle Houses across the Southeast: check.

- Send in generators, RVs, and gas to areas with restaurants that probably will be impacted: check.

- Make sure maple syrup, sausage biscuit and waffle rations are fully stocked: check, check and check.

“We try to plan, and our plan gets us up to the storm. Once the storm hits, we really just react,” said Pat Warner, director of public relations and external affairs for Waffle House. “We try to be nimble.”

Waffle House restaurants are often used to gauge the magnitude of disasters in the Southeast: If a store is open, your community has been spared. If the store is open but has a limited menu, you've probably gotten some damage. If the store is completely closed, you’re in a disaster zone.”

Here, at last, is a clear, plain, punchy English prose - check! - loaded to the brim with information and ideas - check! - light to zero on editorializing - check! Can-do American optimism and determination are abundant. You’ll learn more about hurricane disaster management than anything else you’re likely to read today.

I love it!

Read it all.